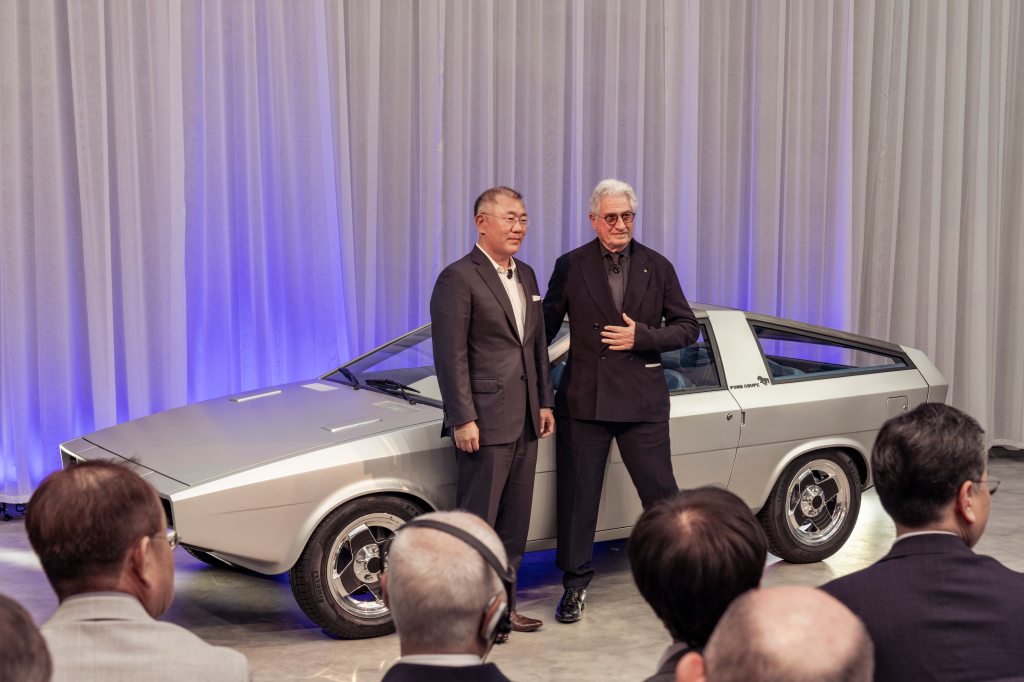

Giorgetto Giugiaro on cars as artworks and finally bringing his 1974 Hyundai Pony Coupé concept to life

Legendary car designer is inspired by the 'brave', out-of-time style of impressionism

If Giorgetto Giugiaro had made it into art school, the Volkswagen Golf might never have been created, James Bond might never have had a submersible Lotus Esprit, Marty McFly might never have travelled through time in a DeLorean and Hyundai might never have made cars.

But Giugiaro failed to make art school and so, reluctantly, went into car design instead. He’s now, aged 84, arguably the greatest living car designer with a host of truly memorable, groundbreaking and beloved vehicles to his name.

He is still designing and creating cars, and recently helped create a running version of his classic 1974 Hyundai Pony Coupé concept, powered by an 80bhp 1.2-litre four-cylinder petrol engine, almost 50 years after it was unveiled at the Turin Motor Show.

But painting is his true joy and passion as the video I filmed with him shows, and the interview below explores in more detail.

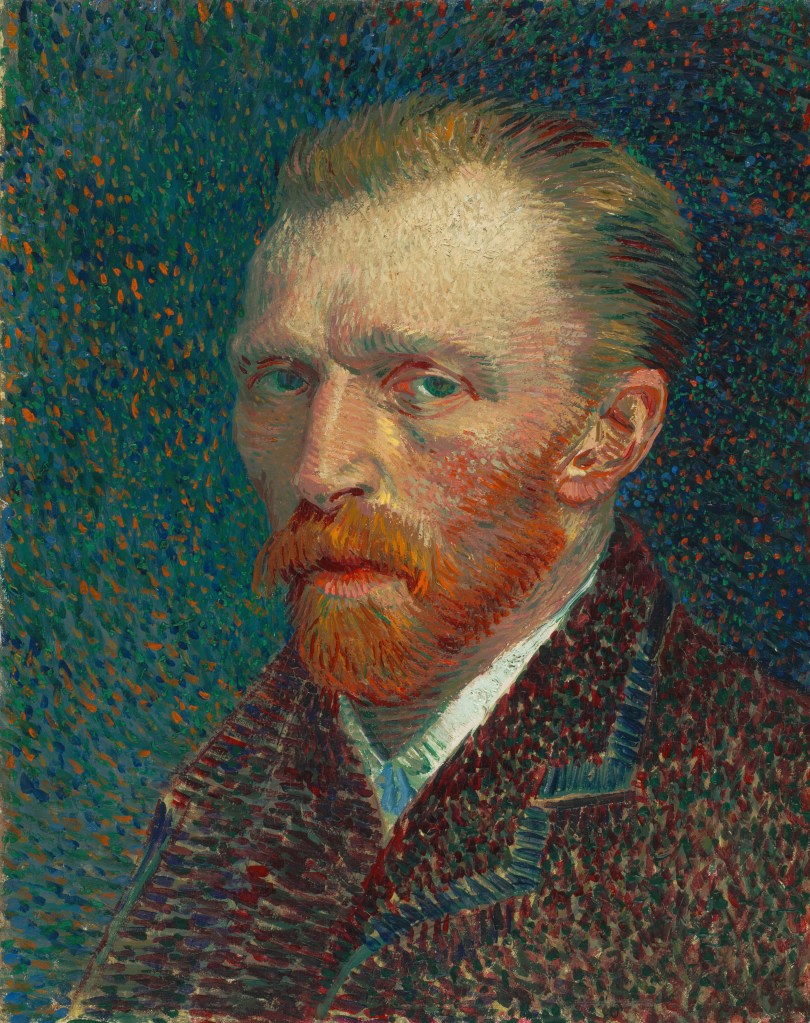

Oddly, asked which artist Giugiaro would like to have collaborated with to make a car, he did not say one of the Renaissance masters such as Da Vinci or Michelangelo; instead he picked Dutch post-impressionist Vincent Van Gogh. That gives an insight into the style of this master of car design.

Jeremy Hart: What was your reaction when you were approached to rebuild the Pony Coupé, since the 1974 original no longer exists?

Giorgetto Giugiaro: It is interesting and also a bit strange to recreate a design from about 50 years ago. Fortunately, I still have some drawings. However, certainly the spirit is different: I am a different age, there is no longer the enthusiasm of youth, my point of view has changed.

Also, technologies have changed; at that time there were very few of them. Doing by hand today what was done back then is more difficult, because all that craftsmanship of those who made the models (e.g., the beaters) has disappeared. Today it is more difficult to do the “old” things, while it is easier to do the overall work thanks to all the computer apparatus.

So, this request surprised me but I’m also happy at the idea of still being able to do such work again.

JH: Do you remember how the phone call went that started the project?

GG: I was in my office with Fabrizio. Of course, I was surprised and a bit displaced. The idea of going to the archive searching for drawings, original photos to reconstruct something that is no longer there immediately won us over.

JH: In general, is there a car that has particularly excited you in so many years of work?

GG: Certainly. The 1955 Citroën DS 19. At that time I was a student, and it was the car that made me finally decide to get involved in car design. It struck me in a special way because it was completely different from all the other cars. To me it is still today a unique car in architecture; it is inimitable.

‘The 1970s was a time when the engineering side had to give way to the vision of designers’

JH: From Lotus to Alfa Sud, you have created so many cars. Where do you place the Hyundai Pony Coupé in this landscape?

GG: Let’s say first of all that the Pony Coupé was born out of research work to show, starting from a widely used car like the sedan (saloon) version, how it was possible to create a product that was more hedonistic and not simply tied to Korea’s needs of the moment.

This coupé gave shape to a vision; the one of a country that with the sedan was beginning to have an original mass-produced and popular product, and that for this reason could also begin to think of other, sportier, more fun products.

I believe it is a project that tells the story of the transformation of a country with a great desire to produce, which — after the necessary — also began to look at pleasure.

JH: If you had to rank them, what place would Pony Coupé occupy in your works?

Being in a non-performance niche, the Coupé was aimed at those who wanted something sporty, brilliant in the aesthetics but on a “normal”, non-performance car. I would not rank it; I see it as a project that looks at sports cars without being a sports car. It is the form of an idea, an attitude.

JH: When Hyundai called you in ’74 to build the Pony, you had to start from scratch — it was all a blank sheet of paper. What was it like to work with nothing behind you? Where did you find the inspiration?

GG: Working on a project means first of all understanding the context in which you operate. In this case, it was a country that wanted to enter such an important sector as the automobile industry with a car of its own design and which started from a base, from an already existing chassis (Mitsubishi’s).

There was a series of industrial constraints to be taken into account: what could be done with what was available in terms of suppliers in a context in which there was no automobile industry with its own established supply chain. So the project was determined by these starting conditions.

When this project was presented, there was also a certain amount of surprise because it was not as advanced as others I had overseen, but obviously it was not possible to make a comparison: the European automotive industry had a history and means at its disposal that could not be those of a fledgling industry.

Pony responded to a need for ease, it had to be comfortable in terms of interior space and trunk space, but it had to be an easy car to assemble because it didn’t have an established organisation behind it.

It was not an easy project to realise but it was very consistent with the needs and the context in which it was to fit.

JH: How do you feel now looking at Hyundai? You participated in the birth of the brand as we know it today, how do you look at your role in this history?

GG: I have always followed them closely, and today they are among the world’s leading manufacturers. I consider it a privilege to be part of such a beautiful and successful story, to have seen its origins.

And of course, it was a great satisfaction to know that the current management wanted to celebrate the beginning of this history and therefore my work. It is not taken for granted that after so many years there is still so much focus on the past and the projects and people who were part of it.

It is also satisfying to still be in business to take an active part in this celebration.

JH: The 1970s: these were special years from the point of view of fashion, music and culture. A great ferment everywhere. What was in the air and what was the automotive world like?

GG: It was a time of creative explosion everywhere, in all directions. In the design field in general it was an effervescent time. It was a time when the engineering side had to give way to the vision of designers, with products driven less by technique and economics and more by creativity. It was a beautiful time, there were social problems, struggles for rights but so much creative momentum in music, theatre, culture and therefore also in design.

JH: In fashion everything is cyclical, so we saw styles from the 1960s and 1970s coming back. How is the automotive world in this respect?

GG: I would say that certain aspects of the past return but they are always revisited, re-read in the light of the present. Also in relation to the technological evolution of the industry; the technological leap we have made does not allow us to go back but the thought, the form, the idea remain.

I think that’s how it is in every industry in the end: taking the best of a certain period and actualising it, contextualising it, while respecting functionality and in a continuous mediation between the inspiration of the past and the needs of the present.

JH: Where do you get inspiration from at the beginning of a project? One designer at Jaguar, for example, said he looks to the female form. Others look to art and the forms of nature. What inspires you?

For me it’s more an ongoing process where you have a dialogue with the past in search of your own originality. With the support of technology that makes possible today things that maybe once were not.

The inspiration is to do something different. There is also an egoistic motion, in a way: to do something that differentiates you from others.

There is also something unconscious in inspiration — all the inputs, the suggestions that come from what is around us — and we assimilate without realising it. And always without realising it we transfer them into what we draw.

JH: All your designs hark back to the Pony style. What was it due to?

GG: One thing you always have to remember about a project is that it is destined to become a product to be marketed. Therefore, it cannot be something too far from expectations, it has to be understandable, recognisable. There is always a product logic that drives everything.

Some people say that Pony is similar to the Delorean. Sure, like I am similar to you. But it is the proportions that make the difference, just like the proportions of the faces that make us all different, even though we all have a nose, two eyes and a mouth.

JH: But Pony was the first car with this design, and it inspired other models such as the Delorean.

GG: I would like to make a small point: a car if it is not produced is not seen. Making a concept for an auto show, as was the case with the Pony Coupé, still means getting this model seen by a small number of people: the insiders; the journalists. Recall that the car then never went into production. Selfishly, when a project is not developed the designer tends to revive it in other contexts.

JH: Hyundai supports the arts with its Art Lab. How do you see the dialogue between art and automobiles, and how does technology integrate with them?

GG: It depends on what we mean by these terms. ‘Art’ is a magic word, it is creativity at the highest level. When I see a structure — the complexity of the mechanical — I think it is unrecognised art. Because for us, art means Picasso or Raphael or other big names. Industrial production has an art content, on the other hand, because there is the same magic that is found in so much canonical artwork.

I am sure that, sooner or later, there will be a discussion about whether it can be considered as an artistic strand. Art, it is true, is a much-exploited word — often misused — but I can say that, in its being beautiful, strong, both feminine and masculine, it is part of the automotive world.

JH: Can you imagine one of your cars displayed in a major museum? The Guggenheim, for example?

GG: I don’t deny that it would be a great privilege but there have been many creative minds in the history of the car who, before me, would deserve to receive this recognition on an artistic level.

Compared to “traditional” works, we have the great privilege that our art is able to move around the world, without the need to go to a museum, being able to be seen simultaneously in Italy, in Japan, in Germany. What artist can boast of a work that travels?

‘Imagining what will happen in the next few years is bordering on the presumptuous’

JH: If Michelangelo and Warhol had been designers, what do you think they would have created?

GG: What a difficult question! Every historical period, even from the point of view of design, has been influenced by so many factors, social and otherwise. What Egyptian architects accomplished in their time, for example, would be unthinkable today.

Today creative processes are much more democratic and collective, especially subject to a set of norms and rules that do not allow absolute individualism. Michelangelo certainly did not need a team of technicians like me! Perhaps from a logistical point of view, but it was he alone who decided the forms his work would take.

JH: If you could choose one artist you would have liked to work with, who would it be?

GG: It is difficult to decide, having knowledge of different eras. The Renaissance is a period that I feel remarkably close to for personal reasons, but at the same time I love Impressionism. It is such a different painting style from the others.

And so brave, because to achieve it, in my opinion, you need to disconnect from the time in which you live, from reality. Van Gogh did not sell a painting in his time, his vision was understood only after his death, and now his works are worth a fortune.

By the way, I am a failed painter, I was one step away from going to art academy, I didn’t want to go into the automotive industry.

JH: In your opinion, how will automobile design evolve in the next 15 years, considering the electric transition?

GG: Imagining what will happen in the next few years is bordering on the presumptuous, because man is capable of devising innovations — more and more amazing technologies. But at the same time, there are other factors, such as war, as we are seeing in these years, that can cause the current progress to change.

At the beginning of my activity as a designer I had seen some American illustrations that proposed a vision of cars in the year 2000: if you took these old sketches from 1955 and compared them with the cars of the year 2000 you would see that there is no comparison. It is difficult to predict human progress.

What I can predict is that man will not physically change and that cars will always be made to suit him.

Jeremy Hart is a long-time contributor to the Sunday Times and is a former presenter of World Rally Championship for Channel 4 and the Dakar Rally. His production company, Timbuktu Content, makes news films including the one provided above.

Related articles

- If you enjoyed this Q&A with Giorgetto Giugiaro you might like to read our 2013 interview with Frank Stephenson, who at the time was McLaren’s chief designer

- Also check out this chat with Ian Callum, Jaguar’s former head of design, on customisations, autonomous vehicles and cars all looking the same

- And don’t miss our review of the Hyundai Ioniq 6, an electric saloon car influenced by classic streamliners

Latest articles

- Peugeot e-308 review 2023: An electric family car desperate to stand out from the family

- Grand Theft Auto VI trailer reveals some of the copycat cars we can expect to drive in ‘biggest video game of all time’

- Brexit tariff delay for British-built electric vehicles

- Vauxhall Astra Sports Tourer Electric 2024 review: Clean-living estate has the manners, but at a cost

- Best-selling cars 2023: The UK’s top 10 most popular models

- Could Alfa Romeo be about to make a dramatic return to Le Mans?

- 7 best windscreen covers to buy in 2023-24

- Toyota previews new electric crossovers amid commitment to multi-fuel future

- First reviews are in after troubled Tesla Cybertruck finally gets handed out to customers